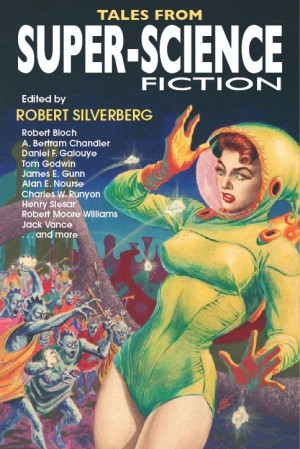

Tales From Super-Science Fiction – Dinged copy

Edited by Robert Silverberg

Illustrated by Ed Emshwiller, Frank Kelly Freas

ISBN-13 978-1893887480

400+ pp. Hardcover

A small quantity of wholesale returns that are slightly “dinged” but definitely cannot be sold as NEW. Act fast if you want a copy!

Robert Silverberg has assembled a collection of 14 stories from Super-Science Fiction. S-SF was launched during the sf boom of the mid-1950s. Paying a princely rate of 2 cents a word the magazine attracted fiction by Isaac Asimov, Robert Bloch, Harlan Ellison. James Gunn, Jack Vance, and Donald Westlake, and featured cover art by Frank Kelly Freas and Ed Emshwiller. Running for 18 bi-monthly issues (Dec ‘55 to Oct ‘59), the magazine eventually devolved into a publication capitalizing on the then-current craze of “monster” stories.

Editor Silverberg traces the genesis of Super-Science Fiction from it’s beginnings as an outlet for numerous colonization/expedition stories to its conclusion with such stories as “Creatures of the Green Slime,” “Beasts of Nightmare Horror” and “Vampires from Outer Space.” It’s fun, it’s cheesy, and we’re really looking forward to it!

Introduction by Robert Silverberg

"Catch 'Em All Alive" by Robert Silverberg

"Who Am I?" by Henry Slesar

"Every Day is Christmas" by James E. Gunn

"I'll Take Over" by A.Bertram Chandler

"Song of the Axe" by Don Berry

"Broomstick Ride" by Robert Bloch

"Worlds of Origin" by Jack Vance

"The Tool of Creation" by J.F. Bone

"I Want to Go Home" by Robert Moore Williams

"Hostile Life-Form" by Daniel L. Galouye

"The Gift of Numbers" by Alan E. Nourse

"First Man in a Satellite" by Charles W. Runyon

"A Place Beyond the Stars" by Tom Godwin

"The Loathsome Beasts" by Dan Malcolm (aka Silverberg)

"Fans of old-fashioned science fiction will delight in this collection of stories from a relatively unknown 1950s pulp magazine. Super-Science Fiction only ran for 18 issues, but for young authors like Silverberg (now a SFWA Grand Master), the magazine’s princely two-cents-a word rate was a gold mine. Silverberg stories bookend the collection: “Catch’em All Alive,” the first story from the first issue, highlights editor W.W. Scott’s enthusiasm for “exploration-team” adventure stories, while “The Loathsome Beasts” follows the magazine’s switch to monster stories, piggybacking on 1950s America’s love for monster movies. Robert Bloch’s “Broomstick Ride” reveals a blasted heath complete with witches on an alien world. “Worlds of Origin” by Jack Vance is a dramatic tale of murder and mystery. James E. Gunn’s “Every Day Is Christmas” sharply satirizes the consumerist impulse. These stories, illustrated with artwork by pulp luminaries like Frank Kelly Freas and Ed Emshwiller, reveal the promise of many now-famous authors at the start of their careers."

—Publishers Weekly

"Knowledgeably compiled and deftly edited with introductory comments by the renowned science fiction author Robert Silverberg, "Tales from Super-Science Fiction" is a 400-page compendium showcasing fourteen of the best sci-fi stories by some of the best authors from the all-to-brief glory days of science fiction pulp magazine 'Super-Science Fiction' which was a bi-monthly publication that ran from December 1955 to October 1959. Beginning with Robert Silverberg's 'Catch 'Em All Alive' and 'The Loathsome Beasts'; to Robert Bloch's Broomstick Ride' and Alan E. Nourse's 'The Gift Of Numbers', all the stories comprising this outstanding anthology are timeless entertainments. Of special note are the faithfully reproduced magazine covers in full color in the end papers. A true treasure, "Tales from Super-Science Fiction" is enthusiastically recommended to any and all science fiction fans and for community library Fantasy & Science Fiction collections."

—Midwest Book Review

"The 1950s were an exciting time to be a young science fiction fan. At the beginning of that decade I was a high school student and the science fiction field was exploding with energy. Two new magazines, Galaxy and F&SF had arrived to challenge Astounding’s long-held spot as King of the Mountain. Over the next few years new titles sprang up like dandelions.

Some lasted only one or two issues. Others enjoyed long and notable runs. Prior to this decade most science fiction book publishing had been limited to fan-owned establishments like Fantasy Press, Gnome Press, and Fantasy Publishing Company Inc. Then, almost simultaneously, the Ace Doubles and Ballantine Books arrived.

By the end of the decade I had got a college degree, put in a few years in the army, married, and gone to work in the computer industry.

Yes. If it was an exciting decade for a fan, it must have been even more thrilling to be a young science fiction writer like Robert Silverberg. (He and I are very nearly of an age.)

In the mid-1950s while I was busy defending the Free World from the Clutching Tentacles of the Red Octopus of Communism, Silverberg was living in a tiny flat in the same Manhattan building as Randall Garrett and Harlan Ellison. Ellison had a good contact with the publisher of two second-line detective magazines. He brought Silverberg around to meet the editor, one W. W. Scott. According to Silverberg’s introduction to Tales from Super-Science Fiction, Scott’s publisher decided to add a science fiction magazine to the line, and appointed Scott as its editor.

Scott knew little and cared less about science fiction, but here were two young dynamos who were enthusiastic about science fiction, knew a lot about the field, and were eager to contribute to the new magazine.

Hence, Super-Science Fiction. The magazine lasted for eighteen bimonthly issues starting with December, 1955. Editor Scott leaned heavily on Silverberg and Ellison, and they responded by furnishing him with a steady supply of stories. Silverberg in particular was featured in every issue of Super-Science, often with several stories in the same issue under a variety of pseudonyms.

Super-Science featured stories by well known authors. Not often the superstars—no sign of Heinlein, Bradbury, or Arthur C. Clarke in its pages. The magazine did manage to snag at least one story by Isaac Asimov (omitted from the present anthology) and Jack Vance (his story, happily, is included in the book).

But issue after issue there would be stories by the likes of James Gunn, Tom Godwin, Alan E. Nourse. They weren’t ground-breaking works and they weren’t their authors’ best efforts. Silverberg reports that Super-Science paid 2¢ a word—pretty good rates for the Eisenhower Era. Top markets—Astounding and Galaxy were paying 3¢; F&SF and sometimes If were on the second tier at 2¢, and the other markets paid a penny a word or even less.

Purely on the basis of pay-rates, Super-Science Fiction should have been a second-tier magazine, but the science fiction world was a pretty tight-knit community half a century ago, and Editor Scott was pretty much of new kid on the block. He did manage to get stories by Asimov, Vance, Robert Bloch, A. Bertram Chandler, Dan Galouye, and other respected, mid-list science fiction authors, but not until they had been cherry-picked by better-connected editors.

According to Silverberg, Editor Scott simply let the leading science-fiction agent of the day, Scott Meredith, know that he was hungry for material. Meredith would send his clients’ works to the highest paying markets in the field, then work his way down through the lesser markets. As a result, Scott habitually wound up with dregs, but they were superior dregs as such things go.

As Silverberg points out, most of the stories in Super-Science were previously intended for other markets. Exceptions were stories by Silverberg himself and Ellison. These two recent graduates from the ranks of fandom had found an editor who would take just about anything they wrote, and they wound up supporting themselves on the odd bounty of this new little magazine.

Of the stories included in the present anthology, James E. Gunn’s “Every Day is Christmas” was clearly a Galaxy story that never made it into that magazine. Don Berry’s “Song of the Axe” belonged on the cover of Planet Stories. Robert Bloch’s “Broomstick Ride,” an odd combination of science fiction and fantasy, seems a natural for F&SF but it wound up in Super-Science instead. Jack Vance’s “Worlds of Origin,” a brilliant Magnus Ridolph yarn, should have been in Startling Stories—but that magazine had expired with its October, 1955 issue, presumably leaving Vance with an orphan manuscript.

As time passed and readers’ tastes changed—and, as Silverberg points out, as the flood of more and more titles overloaded display racks and emptied the wallets of mostly youthful buyers—sales slackened. The number of magazines fell off dramatically, but even lessening competition failed to give sales the necessary boost.

The publisher of Super-Science Fiction tried to jump on the bandwagon of monster magazines that had begun with Forrest J. Ackerman’s Famous Monsters of Filmland, emphasizing the monster aspect of the stories in each issue. But the tactic failed, and Super-Science Fiction disappeared. Its eighteenth and final issue was dated October, 1959.

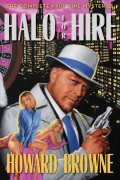

During its eighteen-issue run Super-Science sported covers by Kelly Freas and Ed Emshwiller, both of them highly respected for their work for magazines higher on the food chain. The Haffner Press anthology features an eye-catching Freas cover, recycled from the August, 1958 issue, and a wonderful array of cover reproductions as its end papers. I only wish they had received full-page treatment.

Tales from Super-Science Fiction is a first rate revisiting of a minor but still noteworthy chapter in science fiction history. The major magazines of that past era have been heavily mined for reprints, but it is to be hoped that somebody – Haffner or someone else – will produce a similar book based on some of the era’s lesser magazines: Ray Palmer’s Other Worlds, Larry Shaw’s Infinity Science Fiction, Sam Moskowitz’s Science Fiction Plus, Leo Margulies’ Satellite Science Fiction.

—Richard A. Lupoff, Locus Magazine

"Before we look at the merits of the actual fiction in this sturdy, entertaining, surprisingly illuminating new anthology—whose contents have been drawn entirely from a fondly remembered but essentially minor digest SF magazine of the 1950s—let us unstintingly praise the book’s editor and its publisher. Without their mutual and interlocking contributions, the world would have been deprived of a little treasure. Not to minimize the primary role of the fiction writers involved, but this is an enterprise that owes as much to its curators as to its creators.

First comes editor Robert Silverberg. A living legend, still wittily active and productive, this SFWA Grandmaster was just beginning his career at the time these stories were first published, and was in fact central to the success of the magazine being surveyed, Super-Science Fiction, which ran from 1955 to 1959. He provides an evocative, informative introduction to the milieu, full of history and anecdotes. (Lead-ins to the individual stories too!) His are the eye and hand that selected the nuggets from the composting pages of S-SF for inclusion here. And if he did not in fact actually plant the seed of this book—no details of its eureka inception are given—then he still raised it up lovingly as if it were his own brainchild.

And what of Stephen Haffner, the publisher? By now, simply to state that you are holding a Haffner book should be shorthand for brilliant design and production values, as well as keenly discerned historical significance. The delightful small trim size here echoes a digest magazine. The colorful endpapers reproduce sixteen out of the eighteen total covers for the magazine. (You can of course see them all online at Phil Stephensen-Payne’s fine site, Galactic Central.) Additionally, B&W interior illos from the pages of S-SF complement each story. And the boards and dustjacket and paper stock feel like archival quality. All at a price to compete reasonably with shoddier items from much-larger firms. Bravo!

Now, what of the fourteen stories? From a project like this, we hope above all for obscure wonders, and that’s indeed what we get. Aside from the familiarity of Silverberg’s own “Catch ‘Em All Alive,” which has previously been deservedly reprinted here and there under the original title “Collecting Team,” we get a raft of excellent rarities from seminal Big Names, and some gems from Lesser-Known Writers.

Henry Slesar delivers eerie planetary adventure with a psychological component in “Who Am I?” “Every Day Is Christmas” finds James Gunn channeling black humorist Fred Pohl by way of any number of noir writers. A. Bertram Chandler handles artificial intelligence in “I’ll Take Over,” while Don Berry evokes layers of distant galactic empires in “Song of the Axe.” Robert Bloch prophetically shows magic triumphing over science (our commingled genre’s recent history in a nutshell) in “Broomstick Ride,” while Jack Vance’s Magnus Ridolph series story “Worlds of Origin” merges a murder mystery with anthropological oddness in the patented Vance manner.

Robert Moore Williams, of all unlikely people, effectively plumbs existential angst with “I Want to Go Home.” In a similar vein, J. F. Bone explores cosmological/theological concerns in “The Tool of Creation.” Daniel Galouye sets up a bizarre if slightly guessable ecological scenario in “Hostile Life-Form.” Alan Nourse does a very creditable Thorne Smith riff with the chronicle of two men who swap talents in “The Gift of Numbers.” The derogatory phrase “spam in a can,” used by early US astronauts for helpless test subjects, is prefigured with some emotional resonance by Charles Runyon with “First Man in a Satellite.” An advance scout for the emigrating population of Earth must practice open-faced deceit to help his species in Tom Godwin’s “A Place Beyond the Stars.” Lastly, Silverberg’s “The Loathsome Beasts” illustrates the final slide of Super-Science Fiction into a somewhat juvenile speciality zine.

Aside from their not inconsiderable craftsmanship and entertainment value, these stories prove deeply illuminating about how much SF has and hasn’t changed.

First, of course, modern readers will note the all-male author roster and the homogeneity of protagonists and their worldviews. This uniformity and congruity of writers, characters and readers is no more nor less than just how the field was in this era. Attempts to retroactively criticize such a monolithic front or impose the standards of 2012 upon these tales would be historically ignorant, tendentious, unproductive, and generally dumb. If any reader can’t accept these as artifacts of another age that still possess the power to thrill, then that recalcitrance reveals more about such a reader’s narrow-mindedness and ideological blinders than it does about 1959.

But the very narrowness of the 1950s field gives these stories a kind of consensual power missing today. The approved methods of narration generally employed back then might strike us now as somehow old-fashioned or simplistic, naïve or over-linear. Yet I would argue that the best stories in this book and from this era achieved surprisingly complex and rich frissons with such a circumscribed toolkit. Likewise, certain uniform assumptions about the future of humanity could be made, accepted and then innovatively played with, freeing authors from having to reinvent the wheel every time. Like all well-defined and delimited styles or schools or modes, variation within a framework produced similar but distinct objects for the delectation of those with refined and codified tastes. The field today, of course, caters to the opposite: little specialist niches for every possible desire. Something’s lost, and something’s gained.

But what these stories also exhibit is the absolute continuity of SF tropes down five-plus decades. It’s amazing how the same templates still continue to be used, especially in media SF. The Slesar story could be the script for a Total Recallsequel. The Gunn is the seed of something akin to The Truman Show. Chandler’s AI shows up in Stross and Gibson. Berry’s story could easily take place in a corner of the Star Wars universe. Bloch’s science-versus-magic riff echoes in a hundred fantasy trilogies. Galouye is laying down the lines of the Alien and Predatorfranchises. Bone is predicting something like Aronofsky’s The Fountain. Godwin prefigures Battlestar Galactica. And Silverberg’s concluding piece could be the matrix for every SyFy Channel original movie.

What these authors—laboring for two-cents-a-word and the modest glory and acclaim to be found from a few thousand fellow cognoscenti—achieved was to build up and extend the foundations they inherited from a prior generation into a world-conquering vision that today owns the cultural landscape.

—Paul di Filippo, www.locusmag.com