Don’t Miss

For Charity

Quick Links

CHIEF OF Police Walworth smacked the top of his desk with his hand so hard that the impact sounded like a revolver shot. “I tell you, ‘Deadpan,’ we’ve got to get those counterfeiters soon, damn soon, or the commissioner will have me out on the sidewalk. And the newspapers are howling like banshees!”

His ace detective and closest friend, seated across the desk from him, replied calmly, placatingly: “We’ve been doing everything we can, Phil. After all—”

“We know the stuff’s being made right in or near this very town. Whenever a green-goods dealer or pusher gets picked up anywhere in the state, it traces right back to Springdale! And, worst of all, we even know the two lugs that print it; we’ve got their mugs and prints. And there we stick! No wonder the newspapers—”

“But don’t make the mistake of calling Harry Fuhrman and Jack Fay lugs, chief. They’re two smart boys—too smart. But they can’t keep it up forever. We’ll get ’em.”

“Sure—thirty years from now when they try to cash in on Social Security! It’d be a feather in our caps if we could beat the Feds to them. But me with a force under me that’s all feet and no brains.” He waved a hand despairingly. “And on top of it all I get dragons for lunch.”

“Huh?” Deadpan’s voice sounded startled, but there was no change in the expression on his rugged face; there couldn’t be. Years ago, after a peterman had left nitroglycerine all too conveniently located for the detective to find, a surgeon had given him a face which would pass inspection, but which was as fixed and changeless as a mask.

“Yeah, dragons,” growled the chief. “To be precise, one dragon, green and red, with horrible-looking eyes and horns. And a long tail.”

“Hmm. Where’d you see it, chief?”

The chief glared suspiciously at his subordinate, realized that he had no way, from Deadpan’s expression, of checking that suspicion, and relaxed. “I didn’t see it. Dorothy says she did, says it came after her back in the woods near the house this morning.”

“How far from the house did she see it?”

The chief glowered. “Listen, isn’t it bad enough to have my only kid—and at six years old she ought to know better—start seeing things like that, or telling yarns about seeing them, without your asking screwy questions like how far from the house did she see it?”

DEADPAN DUNN slouched deeper in his chair, put his feet on top of the chief’s desk in defiance of all rules and regulations. “Quit acting like you were sitting on a thumbtack, Phil; I just asked you a straight question. Where did she see it?”

Chief Walworth took a moment to calm down before he could answer. Then he took a pencil from his pocket, went into elaborate detail in drawing a map.

“Maybe,” he began sarcastically, “I should start by telling you how it happened that I drove home for lunch instead of—”

“You can skip that.”

“Thank you too much. So here’s where she saw it. This new property I bought last spring runs back ten miles, mostly wooded. You know the path that runs due north from the house. Well, it was, I’d judge, about three miles out on that path—just at the foot of the hill that that old cabin is on.”

Deadpan nodded. “I know. She was playing by that little crick and—”

“And she’d been playing there for an hour or so, and then the dragon ran down the hill after her. Its head, I am informed, was bigger than a barrel, and it had long green ears. I don’t remember the color of the eyes; shall I call home and ask?”

“You needn’t,” said Deadpan condescendingly. “What did you do about it?”

“What do you think I did about it? Got out a Tommy-gun and went dragon hunting? Bah. What’s wrong with you this morning, Deadpan?”

The detective rose and stretched. “Spring fever, I guess,” he yawned. “Any other little details you remember?”

“Are you taking a course in psychology or dream analysis? Or just nutty? Sure there’s more; halfway down the hill, it came apart in the middle, or broke in half, or turned into two dragons or something.”

Deadpan nodded as casually as though he had expected it all along. He yawned again, then drifted toward the door.

“You’re on that counterfeiting case, don’t forget. And you’re going to stay on it until Fay and Fuhrman are—”

“Startin’ right in, Phil. I’m on my way.”

“Where you going to start this afternoon? You’ve tried every—”

“I started ten minutes ago. If you must know, my next stop will be to question the office help right here in the building, just to make sure.”

Deadpan managed to close the door behind him before the chief could ask him what he wanted to make sure of; he wasn’t quite sure of that little matter himself.

Nick Rapelje, the janitor, was sweeping at the other end of the corridor. Deadpan strolled down near him, leaned against the wall.

“Nick,” he asked. “You got kids, ain’t you?”

The janitor stopped work. “Sure, Mr. Dunn, sure. My Mike, he’s three; my Tony, he’s five and a half; my Polly, she’s—” His hands were making gestures resembling steps.

Deadpan interrupted. “That’s swell, Nick. Listen, and think before you answer this one. Suppose you owned a big chunk of woods out beyond the edge of town, lived in a house in one corner of it. Your Tony or your Polly goes out in the woods alone to play and comes running in at noon saying he or she saw a big red and green dragon. What would you do?”

NICK RAPELJE leaned on his broom, meditated. “Mr. Dunn, if it was my Tony, he’s five and a half, I spank him, good and hard. If it was my Polly, she’s seven, I take her see the doctor.”

“You wouldn’t go out looking for the dragon?”

The janitor shrugged eloquently. “What for I do that, Mr. Dunn? You try to kid me maybe?”

“I’m not exactly kidding, Nick. Just wondering something. Suppose your Tony would go out into the woods to play and wouldn’t come back for lunch. Would you—”

“I take my shotgun, Mr. Dunn, the one I hunt rabbits with last summer, and I go out and—”

“Thanks, Nick. It’s just possible.”

“What’s just possible, Mr. Dunn? You don’t mean that my Tony or Polly may—”

“No, no, Nick. Your kids are all right. Maybe I’m crazy, but don’t let that worry you.” He drifted away from the janitor, laboriously climbed two flights of stairs to the bureau of identification office, sat down on Captain Miller’s desk.

“Don’t let me stop you working, cap,” he drawled. “But if it isn’t too much trouble, tell me what you know about the shady pasts of Harry Fuhrman and Jack Fay. Before they hit the grift.”

Miller shoved back his chair, stopped writing. “Don’t know much about Fuhrman except that he isn’t a local product. Neither is Jack Fay, for that matter, but we know more about him. Came from Frisco.”

“He was an engraver before he started shoving the queer, and then got into making it. But what else was he?”

“Studied art as a kid. Was connected with a couple of theaters for awhile.”

“Actor?”

Miller shook his head. “Backstage work. Prop man, made scenery, that sort of stuff. But that can’t be a lead, Deadpan. There’s only one theater in Springdale besides the squeakies, and besides—”

“I know that, cap. But that’s the dope I was after. It’s crazy, but it fits.”

“What fits?”

“Listen, cap. If your kid—if you got a kid—came in and told you a green and red dragon chased him out of the back yard, what would you do? Would you rush to the window?”

Captain Miller’s jaw dropped. “Is it spring fever, Dunn, or are you really going plumb—”

“Pipe down and answer the question, cap. Would you or wouldn’t you rush to the kitchen window?”

“If my kid told me a whopper like that? I’d rush for the hair brush, that’s where I’d rush.”

Deadpan grunted. “And if the dragon business had been three-four miles away, you wouldn’t go to the trouble to go and see?”

“Not if I was in my right mind.”

Deadpan sighed and started for the door. “It seems to be unanimous, cap. This force is unfair to organized dragons.”

In the front office, Deadpan stopped beside Betty Shires’ desk, waited until her typewriter stopped clicking.

“Listen, beautiful. Were you ever six years old?”

She smiled up at him. “It seems likely. I was five once, and seven. Something must have happened in between.”

“Ever see a dragon?”

Her eyes widened, she looked at him closely—and then remembered. You couldn’t really ever tell whether Dunn was kidding or not; his expression was always the same.

“Don’t think so. I’ve read about them, seen pictures.”

“If you were dreaming about one, or making up a story about one, and it chased you, what would it probably do?”

Involuntarily, she looked at him again, decided to take it seriously. “I’d expect it to spout smoke and fire, maybe; or take off the ground and fly; or—”

“Or come apart in the middle?”

She looked bewildered. “No dragon of mine would do anything like that. I think if I were imagining a dragon, that’s the last thing I’d think of. Dragons don’t break in two.”

“This dragon did,” said Deadpan. He moved away hastily before she could ask questions.

HE slowed down and when he reached the corridor he sauntered back toward the chief’s office. He opened the door and thrust his head into the room.

Chief Walworth turned around in his chair, glowered. “You still hanging around here?”

“Yeah, still here. Say, Phil—if Dorothy had seen human beings near that cabin instead of a dragon, would you have gone out to see what it was all about?”

“Lord love a duck, Deadpan. Are you still raving about that dragon? You’ll be seeing them yourself before—”

“Would you have gone out there—if she’d seen something else? Something reasonable?”

“Sure, you dope. What do you take me for?”

“That isn’t the point, Phil. If she hadn’t come back at all, you’d have gone out, too, wouldn’t you? But for a dragon, nobody would. Not even a red and green dragon?”

“What’s red and green got to do with it? Listen, Deadpan, you need sleep or hot coffee or something. Take the afternoon off and go home and sleep. I got enough worries without you hounding me about—”

Deadpan closed the door to avoid listening to the rest of it. He went to his own desk in the general office, and from the top drawer he took a flat .32 automatic, put it into his coat pocket.

Sergeant Claney, making out a report at the next desk, looked up and grinned. “Going hunting, Dan?”

Deadpan nodded soberly. “By the way, sarge, if you were hunting for a wanted criminal, where’s the last place you’d look?”

“The last place? I dunno. I’d probably start at the hotels and the pool halls; how do I know where I’d look last?”

“It would probably be your own back yard,” said Deadpan. “Have you ever known a criminal smart enough to figure like that? There may be one.”

“Mebbe so.” Sergeant Claney rubbed his jaw meditatively. “I read a book once—”

“It’s a bad habit,” interrupted Deadpan, starting for the door. “Don’t let it get you, sarge.”

Outside the building, he climbed into his roadster and drove out past the city limits to the country home Chief Walworth had purchased the previous year.

The chief’s wife was on the front porch, knitting. Deadpan took off his hat as he climbed the porch steps.

“Where’s Dorothy, Mrs. Walworth?” he asked.

She looked up. “Why, Mr. Dunn. Seems like ages since you’ve— Dorothy is over at her aunt’s. She’s still a little upset over her—her hallucination. Did Phil tell you?”

Deadpan nodded.

“We’ve convinced her that she imagined it. But she was still a little—well, we sent her to her aunt’s for the rest of the day. I’m going to watch her diet more carefully.”

“Has she played there before, Mrs. Walworth? I mean, where she thought she saw it?”

Mrs. Walworth looked at him wonderingly. “Why, no. We let her play anywhere she likes as long as she stays within sight of the house. This is the first time she ever disobeyed and went that far.”

“About that cabin back there, Mrs. Walworth. I know a fellow who wants to rent one like it for a couple of weeks. Is it in good shape?”

She shook her head. “I doubt it. Anyway, it would be awfully dirty. As far as I know nobody has been there this year at all. We just haven’t any use for it and—”

“You won’t mind if I take a look to see if it’s in good enough shape to use, do you?”

“Not at all, of course, but won’t you sit down and—”

Deadpan managed polite apologies and got away, feeling sure he hadn’t awakened suspicion or apprehension.

He took the first two and a half miles at a good pace, then slowed down, leaving the path but walking parallel to it through the woods. When he came to the edge of the glade, he stopped, looked out through screening branches.

There, in the open, was the shallow creek beside which Dorothy had been playing. Beyond the creek, the slope of the hill and at the top of the hill, the cabin.

THE CREEK was quite close to where he stood; he could see the marks in the sandy soil where the child had played. Ruins of sand castles showed that she had lingered long. There were the three flat stones on which she would have crossed the shallow creek, started up toward the cabin.

Moving cautiously now, Deadpan skirted the clearing, crept up to the back of the cabin. One window there had been boarded up, the glass broken. The glass of the other window was so caked with dirt he couldn’t see through it.

He listened for a long time, hearing nothing, before he went around to the front of the cabin, tried the door. It opened easily.

There was no partition in the cabin, and from the doorway he could see that it was empty—empty, that is, of human beings. Its inanimate contents were ample proof that his hunch had been right.

There was a small hand-press in one corner, and, besides the two cots and the oil stove, there were two tables covered with engravers’ tools and equipment, stacks of paper, boxes. . . .

Deadpan put one foot out toward the doorstep, pulled it back. His sharp eyes had caught a glimpse of a fine thread stretched knee-high across the doorway, a black thread so fine as to be almost invisible.

Leaning around the doorpost, he traced the thread as it bent around a nail, led toward the ceiling above the doorway. Then, standing well outside the door, he broke the thread with a thrust of his foot, heard the thud and saw the fall of the heavy sandbag from the ceiling above the door.

He rolled it aside and went on into the cabin, crossed to one of the tables where the gleam of copper plates had caught his eye.

He was still engrossed in studying the intricate beauty of the engraving on those plates when the two shadows appeared in the shaft of sunlight that came through the open doorway. He dropped the plate, whirled, but a quiet “Don’t try it” stopped his gesture toward his pocket. That and the sight of the revolver muzzle that aimed straight at his belt buckle, too close to miss.

Deadpan raised his hands.

The shorter of the two men stepped behind him, slipped the automatic from the pocket of his coat. Expert hands ran over him in search of another weapon, took a pair of handcuffs from his hip pocket.

“I told you that scaring the kid away wouldn’t work,” said the taller of the two men. His voice was calm, but bitter. “Here we have a bull prowling around the same afternoon.”

The other shrugged. “What did we have to lose? If we’d let the kid come up here, or if we’d bumped her like you wanted to—well, we’d have had to lam anyway. What did we lose?”

The tall one grunted. “Well, this place isn’t useful any more. If we bump this one, more’ll come to find out why. Pack up the plates while I hold the heat on him.”

The other held out the cuffs. “We got to work fast. Put these on him and then help pack the valuable stuff. We’ll tie him good when we’re through, and leave him to guard the rest.”

“Okay. Snap ’em on and then get the key.”

Deadpan lowered his hands, held them out for the cuffs. The smaller of the men stepped forward, staying out of the line of fire. Deadpan didn’t move, as the first cuff snapped into place; the second. He was counting on—

And he anticipated rightly. At the click of the second handcuff, the vigilance of the man behind the gun relaxed momentarily. The hands of the other were still at the detective’s wrists. With the suddenness of a striking snake, the detective went into action.

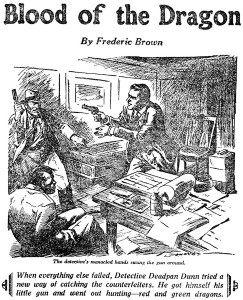

HIS HANDCUFFED HANDS grasped the coat-sleeves of the man who had just snapped the cuffs, swung him around directly in front, in the line of fire. Then he suddenly pushed with all his weight, shoving him backwards against the gunman.

The first man went down. The detective was past him in an instant, and before the deflected gun could be swung toward him again his manacled fists lashed out together, straight for the gunman’s chin. The man went down; the gun clattered on the floor.

The detective’s heel came down on the fingers of a hand that clutched for the gun. Then he had it himself, swung around in time to blast his own automatic from the hand of the smaller of the two counterfeiters, who had just yanked it from his pocket.

The automatic dropped as the counterfeiter clasped a shattered right wrist. Suddenly the room was silent.

“Okay, boys,” said Deadpan. “Go ahead and pack the plates, just like you were going to. We’ll take ’em along.” He waved the weapon ominously. . . .

Chief Walworth looked up as Deadpan reached across his desk for one of the chief’s Havanas. “I get it all,” the chief admitted. “All but one thing. The kid plays at the creek in sight of the cabin. They know if she comes on up, it’s gotta be curtains for them or for her—or both.

“This Jack Fay is an artist, has made scenery and stuff and gets the idea that if they can scare the kid away to tell some yarn nobody’ll believe and that won’t be investigated—they got a chance to keep on using the cabin.”

Deadpan lighted the fragrant cigar, inhaled deeply. “Sure, and a swell spot it was, chief. Who’d have thought of looking for ’em in your backyard, practically? And Fay came from Frisco. He’d probably seen dragon parades in Chinatown. Chinks make papier-mâché ones, use ’em on holidays.”

The chief nodded slowly. “It all fits. But what I can’t dope out is what gave you the hunch. Something must have tied up in your mind between the dragon gag and—”

“Yeah. It was just a sudden thought when you said the dragon was red and green. Remember? Well, counterfeiters would have gobs of green ink, wouldn’t they? And as for red—”

Deadpan took an envelope from his pocket; from it he poured onto the desk a little pile of dark-red powder.

“Varnish makers,” he said, “use that stuff to color varnish, and all engravers use it, use lots of it. And mixed with water, it’s a swell red pigment.”

Chief Walworth gazed at the little pile of red powder.

“Yeah, but where’s the hunch?”

Deadpan exhaled a cloud of smoke, yawned. “Just a coincidence, chief. The stuff is known commercially as dragon’s blood. . . .”

THE END

Copyright© 2015 Haffner Press