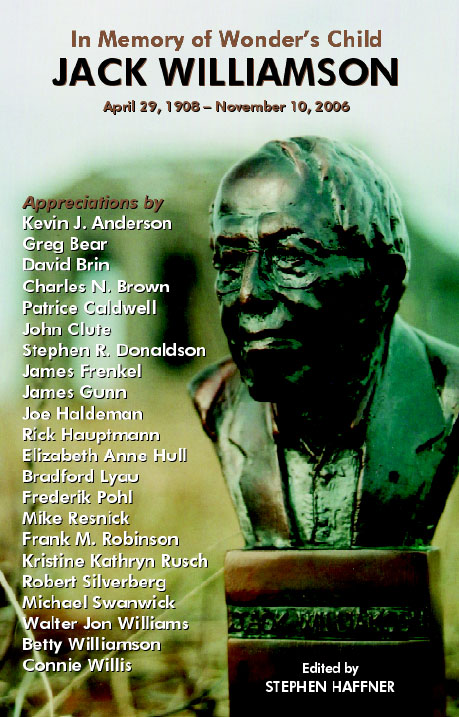

Chapter II

The Spheres from

Below

A

HALF-HOUR before midnight on May twenty first the

fourth light shaft should appear and that’s just six hours from now!”

It was Dr. Kelsall who spoke and as he

replaced in his pocket the watch at which he had been glancing we four

turned for the moment from each other, gazing about us.

Around us there stretched away in all

directions the vast green solitude of the Brazilian jungle, a

tremendous solid mass of vegetation that seemed to lie like a great

blanket over the earth.

The great close packed trees, the thick vines

and lianas that bound them everywhere together, the impenetrable

plant-life that choked the lower ways between them, swarming with

brilliant hued birds and monkeys and strange insects, with larger

animals stirring beneath—these extended out from us on all sides, lit

now by the waning glory of the sunset to the west. The whole scene

about us impressed one most with the illimitable fecundity of the life,

plant and animal, with which it swarmed. It was a fecundity of life so

dissociated from anything human that it was strangely depressing.

We four, however, were standing upon an island

in that ocean of green thick life—a long triangular shaped clearing of

brown earth and sand, which was bounded on two sides by the broad ochre

floods of two swift-running rivers, the Malgre and the Tauraurua. These

flowed together at the point of our long triangle clearing, continuing

on their course as one to the great Amazon away to the south.

It was somewhere on or near this triangle of

land between the two rivers, according to Kelsall’s calculations, that

the fourth of the strange light shafts would appear if it appeared at

all. So it was toward one side of the triangle, along the Malgre’s

shore, that our brown tropical tents were pitched, our long river skiff

moored beside them.

It was in that long sturdy craft and by virtue

of its strong little motor that we had made our way up the Malgre to

this point where the Tauraurua flowed into it. The swift airliner we

had managed to catch had brought us from New York to Para in less than

two days.

Then, procuring the stout river skiff that was

large enough to hold us and all our equipment and apparatus, we had

proceeded up the Amazon by river steamer to the point where the Malgre

flowed into it. There, leaving the steamer, we had begun the most

toilsome part of our journey, the slow fight upward against the

Malgre’s current through jungles that stretched, to the north to and

over the Guianas, jungles swarming with animal life, their only human

inhabitants a few half glimpsed brown Indians.

It was the great wilderness of the Brazilian

Guiana into which we were penetrating. So toilsome was our progress

that had our goal been but little farther we could never have made it

before the calculated time.

As it was it was only on the preceding day

that we had reached this triangle of clear land. Until the present

moment we had been busy in arranging apparatus, which had given us

anxious moments in our rough journey upward in the skiff, for much of

it was of a super sensitive and delicate nature.

There were black cased cameras, cinema and

still types, some equipped with various ray filters and screens. Square

fluoroscopes lay ready beside the delicate galvanometer circuits and

electroscopes that had been set up by Fenton and myself.

If a fourth great light shaft appeared near us

it would be strange if we four, with the comprehensive equipment which

we had set up, would not be able to record the shaft’s appearance. We

should be able to determine, even though it lasted but a minute or two

like the others, its nature, whether electrical or radio active or

simply light.

We were ready indeed for the coming of the

fourth light shaft, yet now as we four stood there, brown garbed, white

helmeted figures with heavy automatics swinging always at out hips, it

was with oppressive doubt that I gazed about me. The whole vast wild

scene about us filled me with misgivings.

Had we come after all on a wild goose chase?

Had the appearance of those three light shafts been due only to some

freak of natural forces, the regular progression in time and space of a

mere coincidence? Had Kelsall been far afield in his belief that here

where we stood another light shaft would appear within a few hours?

These were the questions that troubled me as

we stood there together, watching in silence as the sunset westward

flared and faded. At last, turning to the others, I expressed some of

my doubts.

“The whole thing seems incredible, doesn’t

it?” I asked. “Incredible for us to expect a fourth light shaft to

appear at this exact spot.”

I indicated with a wave of my hand the thick

walls of jungle that rose around our river bordered clearing and

Darrell and Fenton gazed silently around at my gesture.

Kelsall, though, shook his head. “No, Vance,”

he said. “If a fourth light shaft appears it will do so here and at a

half hour before midnight. I’m certain of that—for the appearance of

the other three have been superhumanly exact in time and place.”

“But there’s nothing unusual here,” I said.

“We’ve explored this clearing and the region immediately around it and

we’ve found nothing unusual—no sign of the presence of human life even.”

“There was nothing strange or unusual at

Kismaya, or south of Moram Island, or before the Callarnia,” Kelsall

reminded me. “Yet the light shafts appeared there. And though no other

humans lie within leagues of us I think that there is nothing human

behind the mystery of these light-shafts which we have come here to

solve.”

“But our plan of action?” questioned Darrell.

“In case the fourth light shaft does appear it will last only for

seconds and we’ll need to be quick if we’re to gather any data on it in

that time.”

KELSALL nodded. “Yes, Darrell, and for that

reason we’ll take up separate stations when the time approaches. I want

you and Vance here to take up a position at the north or broad end of

this triangular clearing, just at the jungle’s edge.

“You will hold the two cameras, ready to turn

them upon whatever spot the fourth shaft appears if it does appear.

Vance, who like Fenton is a physicist and understands such work better

than we, can use the fluoroscopes to determine whether the shaft is

fluorescent in nature.

“Fenton and I, on the other hand, will station

ourselves down at the clearing’s point on the open sand. There Fenton

can watch his electroscope and galvanometer circuits while I use the

spectrograph on the light shaft.

“In this way if the light shaft appears in

this vicinity as it should, even though it lasts for but a minute, we

should be able to determine accurately its nature and gain enough data

to enable us later to discover its cause.”

“You have no theory yourself as to that cause,

then, Kelsall?” asked Fenton curiously. “You’ve never ventured any to

us but you must have some thought concerning it.”

Kelsall’s face grew grave at the question. “I

have a theory,” he said slowly, “but not one I want to mention now. It

is a theory which to my mind can alone account for the appearance of

these strange shafts of right. Yet it is so startling, so insane, that

even you could not take it seriously now.

“But if another light shaft appears here, if

we cannot discover its nature, it may be that the thing that has

suggested itself to me will be corroborated by our evidence. And if

that is so—”

He did not finish but as Darrell and Fenton

and I stood there beside him, regarding him, something of the strange

suspense that held him was communicated to ourselves. So it was in

silence that we stood there, while the last colors of the sunset faded

westward, while the deep tropical twilight stole westward across the

world like a veil drawn after the descending sun.

Swiftly then the darkness of night, soft and

velvet, was upon us with the brilliant constellations of the equatorial

sky burning out brightly overhead, with a strange tremor and stir of

renewed and re awakened nocturnal life. Soon now would be upon us also

the moment for which we had trailed to this spot. We began to follow

Kelsall’s orders, to arrange ourselves and our masses of apparatus

about the long clearing.

At the long triangular clearing’s northern

end, its broad base in effect, Darrell and I quickly set up our cameras

and fluoroscopes, just at the edge of the thick wall of the jungle.

That base or side of our triangular clearing was perhaps three quarters

of a mile in width and from it the clear triangle of ground stretched

southward, bordered on either side by the two swift rivers, to the long

sandy point where they converged.

It was upon this tip that Kelsall and Fenton,

in turn, set up their own apparatus, their spectrographs and electrical

apparatus, Darrell and I helping them and working without hamper in the

clear thin starlight that lit all the clearing. This done, the four of

us met again for the moment at the clearing’s tenter before taking up

our positions.

Kelsall clasped the hands of Darrell and

myself strongly. “Darrell—Vance,” he said, “I know that you will do

your best on this. Be ready and if the light shaft does appear anywhere

within sight of us get your instruments on it at once.”

Darrell nodded, raising his hands for the

moment to the shoulders of Kelsall and Fenton. “We’ll be ready for it,”

he said. “And if nothing happens—well, we’ll have done our best.”

With these words we turned and then the four

of us had separated, Darrell and I striding toward the clearing’s

northern jungle-wall, where our instruments lay ready, while Kelsall

and Fenton started for the sandy tip that was to be their position.

We had retained our heavy pistols, the

profusion of fierce wild life in the jungles about us making that a

necessary precaution. We crouched down among our instruments. Our list

preparations had been made and our wait for the appearance of the

fourth light shaft began.

A glance at my watch showed me that there

remained still more than two hours before the coming of the moment, a

half-hour before midnight, which Kelsall had calculated as the time of

the next shaft’s appearance. We had begun our watch thus early at his

own suggestion, in case his calculations might have been a little

inaccurate.

WE WAITED in silence. Far down at the

clearing’s tip we could make out in the starlight, the vague shapes of

Kelsall and Fenton, crouched likewise with their own equipment, and as

silent as ourselves.

I found myself listening to all the myriad

strange sounds that came from the thick jungle behind us, the distant

coughing snorts or dull trampling sounds of large animals, the shrill

sounds of countless insects, the occasional swashing of large lizards

or reptiles in the rivers to east and west.

The sullen heat of the day, the burning heat

of the equator, had declined only a little with the coming of darkness.

And as the minutes dragged past with no other sight or sound save those

of the profusion of jungle life about us, as the great tropical

constellations sloped majestically across the sky, to my physical

discomfort was added the return of my troubled doubts.

IT SEEMED to me incredible that we four should

have found reason enough in the facts Kelsall had discovered to bring

us to this wild spot in anticipation of witnessing a repetition of the

three phenomena that had already occurred. It seemed insane for us to

expect a fourth of the strange light shafts to appear at exactly this

spot, at the exact time that he had calculated.

And as that time slowly approached, as my

watch’s hands steadily approached the position that would mark the half

hour before midnight—as no slightest unusual sight or sound came from

anywhere about us—I felt my doubt becoming stronger and stronger.

With watch in palm, I watched the larger hand

slowly moving toward the half hour position. Only minutes remained

until our calculated moment would arrive. Slowly, minute by minute, the

hand moved, was within a half dozen minutes of the half hour, yet from

about us had come nothing new.

Now it was within four minutes, three, two,

one. Tensely Darrell and I were watching it, The hand moved at last

within a single minute of the awaited moment. Our hands were clenched

unconsciously with suspense.

Then at last, with infinite slowness, the hand

moved to the half hour position. Our nerves taut with suspense, our

hands ready on the instruments before us, Darrell and I waited, gazing

about us, gazing at—nothing! No single gleam of light had appeared in

that moment in all the dark mass of the jungle about us and behind us,

no light shaft or sign of one!

Gazing for the moment at each other, sick with

disappointment, Darrell and I rose to our feet while down at the

clearing’s tip we saw Kelsall and Fenton rising even as we did. We had

failed. Our plan, by which we had thought to solve the mystery of these

strange light shafts, had proved futile after all.

I took a step forward to go down to Kelsall

and Fenton, disappointment wrenching at my heart. A single step I took

and then, abruptly, I halted in my tracks. At the same moment a hoarse

cry burst from Darrell behind me.

There before us, at the center of our great

triangular clearing, half way between ourselves and our two friends,

there stabbed suddenly upward a terrific beam of brilliant blue light

whose dazzling intensity seemed blinding to my eyes!

Fifty feet upward from the clear ground of the

clearing it towered, a tenth of that in diameter.

Even as I shrank back from its soundless

appearance, even as I heard the cries of Darrell and Kelsall and

Fenton, I saw that near the shaft’s top, set in some strange way, a

circle or disk of pure white light, as brilliant as that about it! As

it appeared I could see by the inset white spot of light that the great

dazzling column was slowly turning as it towered there, turning like a

solid revolving shaft!

In the single instant of the beam’s appearance

I glimpsed these things, then leaped back to the black fluoroscopes

which in the next moment I trained upon the shaft. Beside me I heard

the rapid clicking of Darrell’s cameras, knew that even at that same

instant Kelsall and Fenton would be working with their own instruments.

Because they were a modern recording

development of the oldtime visual fluoroscopes I knew that if the light

before us was of a fluorescent nature that fact would be recorded

instantly upon their screens. So I swiftly exposed them, one after

another, to the great towering shaft of blue brilliance that loomed

before us.

Surely that scene must have been one of

infinite strangeness—the tropic night all about us, the awful giant

beam towering there so strange and terrible, the figures of us four to

north and south of it, standing out like all things about us in its

blue glare, and working like madmen with our instruments to record all

available data.

Around and around the thing turned for more

than a minute, the white light spot upon its blue brilliant column

moving with each turn. But the minute seemed to us drawn into hours.

Then abruptly, as strangely and swiftly as it had appeared, it seemed

to flash downward, to vanish like an extinguished light.

We were left there in a darkness that seemed

deeper than before!

“It came—as Kelsall thought—but in God’s name,

man, what can it be?”

“Whatever it is we’ve got our data!” said

Darrell. “And there come Kelsall and Fenton now—”

KELSALL and Fenton had risen and were striding

excitedly toward us, calling to us in answer to our own shouts as

Darrell and I strode to meet them. They were within a few hundred yards

of us when a thing happened the mere memory of which sickens me to this

day.

In one lightning instant the thing happened.

There was a gigantic stabbing flash of yellow light that flared for a

moment blindingly before us. At the same instant there broke from about

us a titanic thunderous detonation that was like the crash of colliding

planets!

Slammed down against the ground by that

terrific detonation, we were aware in that instant of only the stunning

light and sound loosed before us and then the thing was over, an almost

thunderous silence following. But before us now, between our two

groups, there yawned in the clearing’s surface the black mouth of a

great shaft or well, five hundred feet in diameter at least and

perfectly circular in shape!

As Darrell and I staggered to our feet at its

edge and stared downward into it, even as Kelsall and Fenton were

staring tremblingly down on its other side, we saw by the starlight

which fell into it that the great shaft dropped down to depths

inconceivable.

Mechanically, unthinkingly, we stared down

into the great shaft, noting only that it was as perfectly cylindrical

in shape as though bored by a giant drill, that its smooth sides, cut

unerringly through rock and soil alike, fell vertically downward to a

point where even the white starlight from above could not illumine the

tenebrous depths! Then, as we stood there, I cried out inarticulately,

pointed downward.

In the awful blackness of the great shaft’s

depths a tiny point of white light had appeared, was growing larger!

Even as we gazed toward it we glimpsed other light-points appearing

beside and around it, other little white lights there far,

inconceivably far, beneath, growing larger with each second as at

immense speed they rushed up toward us!

Growing larger until in moments more, as we

gazed, we could see that the white lights were flashing upward from

dark round objects that were racing up the shaft toward us! And in the

next moment we recognized them as great metal spheres!

Each a full twenty five feet in diameter,

massed together in a swarm of a full hundred or more, they were

rocketing up the shaft toward us! From each of them flashed a white

beam of brilliant light by means of which they held their course

straight upward through the great shaft!

Racing up toward us at speed unthinkable—and

as they shot up with a humming sound, there came to my stunned ears a

wild cry from Kelsall, standing there across the great shaft’s rim from

ourselves.

“Spheres!” he was crying madly. “Sphere-ships

from inside the earth! Darrell—Vance—I see it all now. Get back, for

God’s sake, get back from the shaft!”